Recent proposals to reform the rules of the House of Representatives included measures to make it easier for legislation that has the support of a majority of the chamber to advance to the floor or prompt committee consideration. If implemented, would this make a difference in how legislation plays out? Apparently, yes.

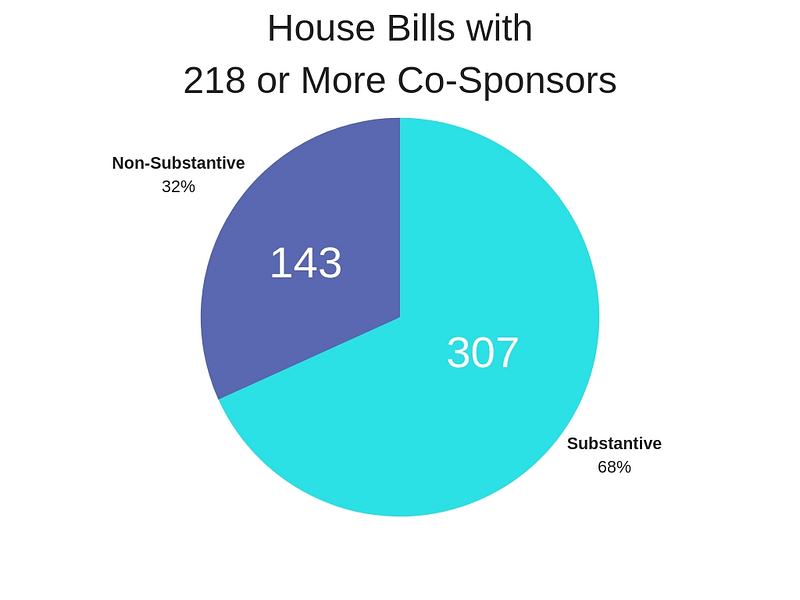

To find out, we reviewed all House bills that had 218 or more sponsors between 1999–2016, i.e., the 106th-114th Congresses. In the House, 218 members constitutes a majority, so for simplicity’s sake we’ll refer to this set of bills as “popular House bills.”

During the 106th-114th Congresses, 108,086 bills were introduced, but only 3.5% were enacted, or 3,728 bills. In the same period, 450 popular House bills were introduced, with 22% enacted, or 102 bills.

In other words, a bill with 218 co-sponsors is six and a half times more likely to be enacted than any particular bill.

Substantive vs Non-Substantive Legislation

While this isn’t particularly shocking, we were surprised to find that, of the popular House bills, two thirds contained ‘substantive’ legislation, i.e., 307 bills. If enacted, they would have made some kind of significant policy change. Conventional wisdom would suggest that most legislation with this many co-sponsors is non-substantive, but that turns out to be incorrect.

The remaining 143 bills, which we deemed ‘non-substantive,’ concerned matters like gold medals, commemorative coins, memorials, recognition, re-namings as well as most House resolutions. (Note: House resolutions related to establishing committees or proposing amendments to the Constitution were included in our tally of ‘substantive’ bills.)

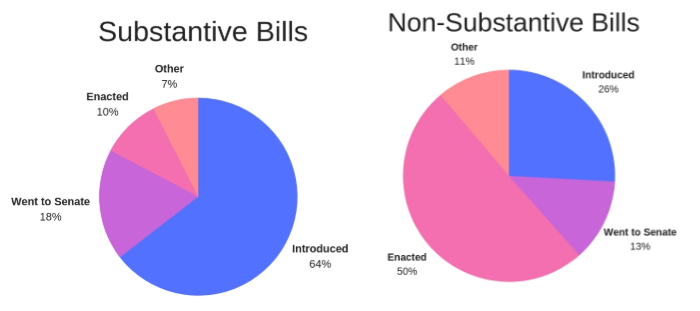

Out of the 307 substantive bills, 28% (86) were enacted into law or advanced on to the Senate, while, of the remainder of the substantive bills, two-thirds (198) didn’t move beyond introduction. For the 143 non-substantive bills, almost two-thirds (90) were successfully enacted into law or moved on to the Senate.

Note: “Other” encompasses bills that were classified as “agreed to (concurrent resolution)”, “agreed to (simple resolution)”, “failed cloture”, “failed under suspension”, “ordered reported”, “parts incorporated into other measures”, “passed the Senate with changes (back to the House)”, and “vetoed & override failed in House.”

The enacted substantive bills primarily related to the following issues: healthcare and health research (10 bills), veterans and police affairs (4 bills), and Iran affairs (4 bills). Other legislation addressed issues ranging from combating animal cruelty to housing regulation and the economy.

What does this mean?

Had this rule been in place over the last two decades, it seems likely that more substantive bills would have moved through the process. By our tally, 198 popular substantive bills didn’t move beyond introduction.

Now, it could be that members would be more careful regarding the bills they co-sponsor, so the number of co-sponsored substantive bills decreases. If so, those that get close to 218 probably would become much more likely to advance out of the House. This likely would prompt leadership to put more pressure on members to not co-sponsor substantive bills. It also might prompt more close tracking of co-sponsors of a measure.

On the other hand, members might view co-sponsorship as a meaningful tool to move legislation, and there’d be more efforts to increase the number of co-sponsors. This would move power back into the hands of the rank and file.This might prompt committees to act on legislation, if for no other reason than to take the steam out of co-sponsorship efforts and give popular measures a fair shake.

What we’re describing with co-sponsorship is possible in the sense that a discharge petition (at least in theory) can force a measure to come to the floor. Yet, there are only eleven discharge petitions in the 115th Congress, and were only six in the 114th. There are other limitations on discharge petitions — political, procedural, and psychological — that significantly decrease the likelihood that such a process would be used.

Our survey is incomplete, of course. It doesn’t explore how getting close to 218 co-sponsors can put pressure on leadership to move legislation. It doesn’t delve into circumstances where committee chairs refused to release legislation with more than 218 co-sponsors (such as with ECPA). It does not look at the relationship between bipartisan support and moving legislation. There’s more research to be done, probably by political scientists, but this does provide a good first approximation.

Our raw data is available online here as a CSV. Thanks to GovTrack.us for the underlying data, which we enriched.

— Written by Amelia Strauss and Daniel Schuman