Of the $4.7 trillion proposed federal budget for FY 2020, $1.4 trillion is discretionary spending, that is,optional spending made through appropriations bills. Before Congress can spend that money, it is divided into 12 slices—one for each of the 12 appropriations subcommittees. These slices are called 302(b) allocations.

Lawmakers are supposed to agree on 302(b) numbers early in the appropriations cycle, but this time around the agreement was (very) delayed. Without finalized topline numbers, lawmakers weren’t able to negotiate over the line items in the spending bills; after all, how could they dole out funds if they didn’t know how much money they were working with in the first place?

Since Fiscal Year 2020 started on October 1st, lawmakers have pieced together short-term-spending agreements, or continuing resolutions, to keep the government’s lights on. Lawmakers finally agreed on final 302(b) numbers for FY 2020 at the end of November, and earlier this week Appropriators introduced two minibus bills that will keep the government funded for the remainder of FY 2020.

So, what do the numbers tell us?

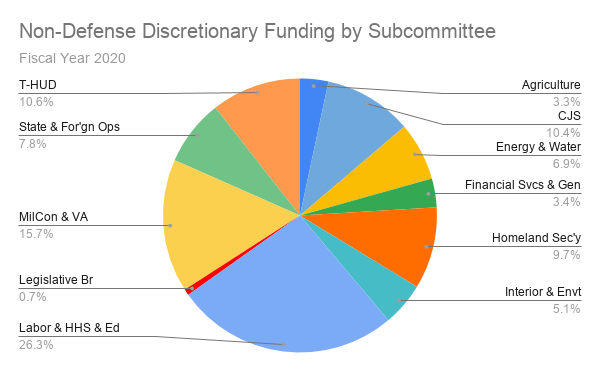

Congress Has A Tiny Slice Of The Spending Pie

As usual, the Legislative Branch had the smallest allocation, at 0.7% of non-defense discretionary funds.

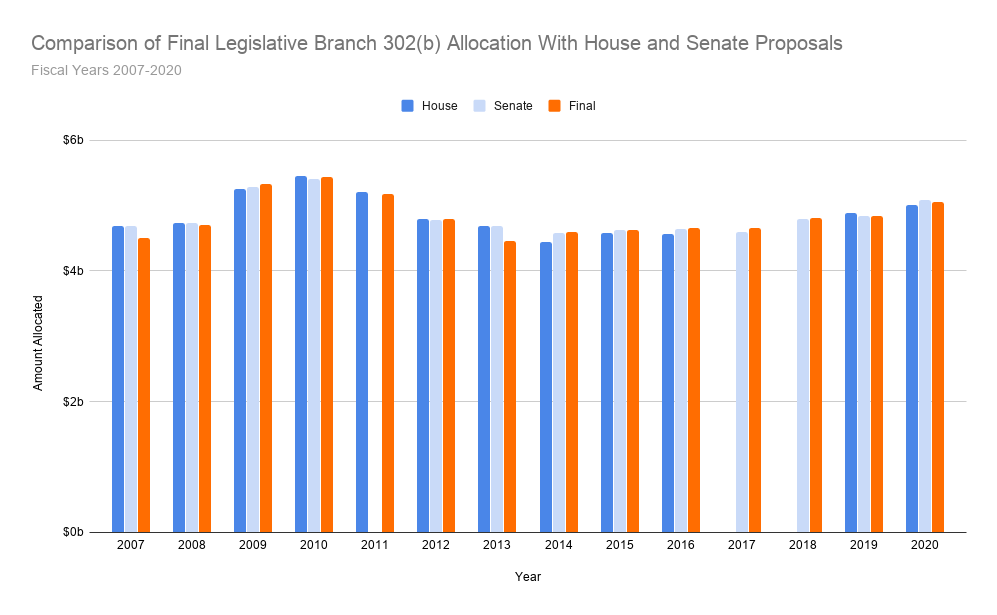

The House and Senate agreed to $5.049 billion in funding for the Legislative Branch for FY 2020; the House had initially proposed $5.010 billion and the Senate had proposed $5.092 billion. In other words, the House had proposed to increase legislative branch spending by 3.6% and the Senate had proposed a 5.29% increase, and they met in the middle at 4.4%. The following chart shows proposed funding levels for the Legislative Branch over the last decade.

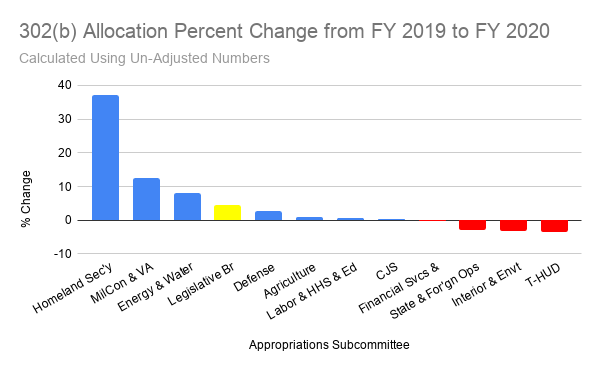

Legislative Branch funding will go up 4.4% from last year (not adjusting for inflation). Notably, that’s below the average 4.98% increase in funding that all other non-defense subcommittees experienced.

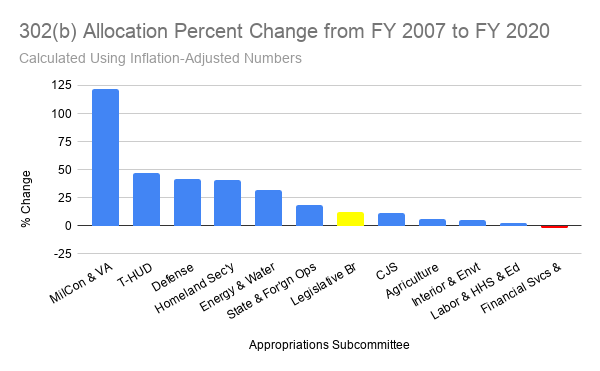

Overall, who are the big winners? Both in the last year and over the last decade, it’s defense and security-related spending that has gone up by a double-digit percentage.

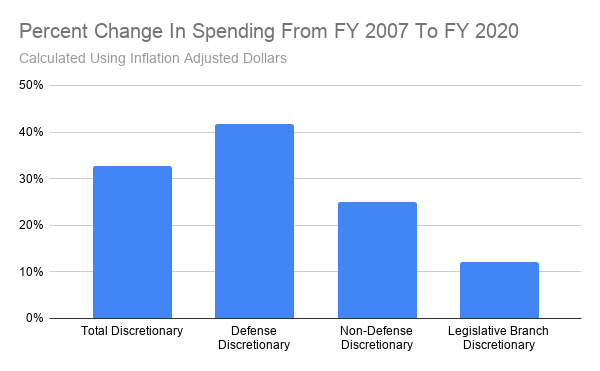

Adjusting for inflation, while overall discretionary spending has increased 32.8% since FY 2007, and non-defense spending has increased 25%, spending for the first branch of government has only increased 12.1% in that same period. That’s second class funding.

Why Is This A Problem?

Let’s break it down: if all discretionary funds ($1.4 trillion) were represented as $100 that appropriators have to allocate, $50 goes to the Defense subcommittee. The remaining 10 subcommittees that roughly correlate with Executive Branch agencies get $49 of the $50 left for non-defense. Congress (and all the Legislative Branch support agencies) get about 50 cents.

With just that 50 cents, Congress has to make all of the laws and oversee the entire federal government (the other $99.50). In reality, Congress can’t spend all 50 cents on those efforts. Some of that money (about 5 of the 50 cents) pays for the U.S. Capitol Police to keep the Capitol Complex safe. Speaking of the Capitol Complex, keeping it standing is also costing Congress a pretty penny in renovation expenses and overrun costs. At the end of the day, Congress can only spend so many of its discretionary dollars on policy staff.

What Should We Do About It?

Whether overall government spending increases or not, appropriators need to increase the portion of funds allocated to the Legislative Branch. Without more funds, Congress doesn’t have the capacity to oversee and stand up to the Executive Branch. The current state of play is that Congress is out-manned and out-gunned and the situation only seems to be getting worse. To preserve the structural integrity of our democracy, Congress must have access to the resources necessary to reassert itself as an equal branch of government.

Check Our Work

Have questions about where we got these figures? There is no comprehensive public-facing government source for these numbers, so we created our own—check out our 302(b) allocation database here. For this article, we used House figures where we were unable to locate the final 302(b) allocation.

Let us know what you think at Amelia@DemandProgress.org.