The U.S. Capitol pre-expansion in 1846.

Is our representative democracy dying? Daniel Stid writes “the idea of representative democracy” is “on the ropes” in the lead to his thoughtful article exploring whether a representative democracy is still workable. He notes that public opinion is “giving it a beating.”

Stid suggests that “both the process and the outcomes of … encounters [between legislators] are invariably less than we hope for, especially when we examine them closely.” And, even worse, maybe there’s a problem with representation itself. “We don’t like decisions to be made on our behalf, especially when we can’t fully track how the decisions are made, and even more so when we don’t fully agree with the outcome.” He closes with a plaintive call for solutions… or at least ways to cope.

I’m not sure anyone has put together a comprehensive solution, but I have a few ideas about a path forward. Much of my experience is in the US federal context, so I am going to use that as a framework. To begin, we need to separate the public’s perception of Congress from what it actually does.

Congress’ Public Relations Problem

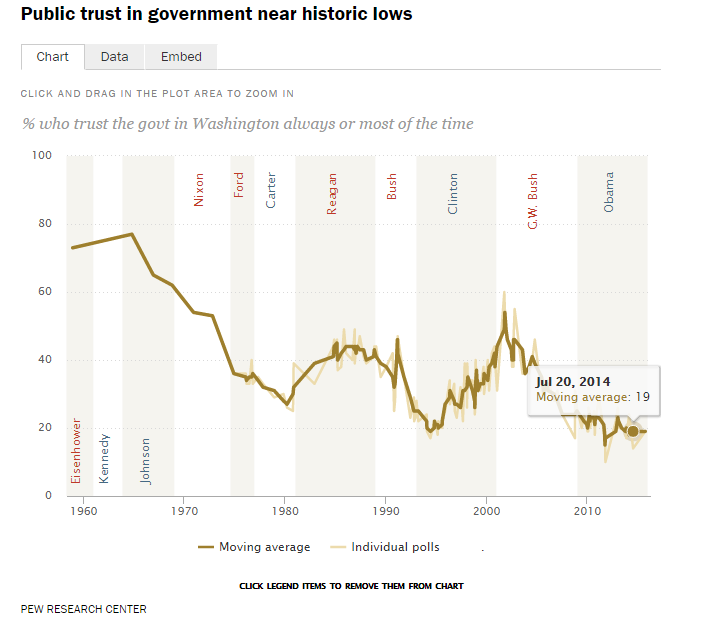

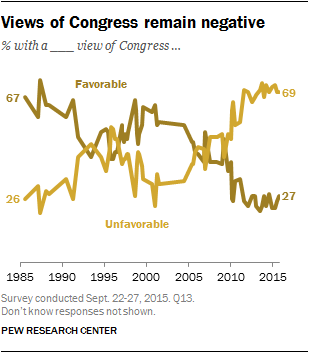

Congressional favorable job approval ratings hug the low teens according to Gallup, while they had previously hovered in the mid 50s during 1998–2004 —spiking to 84% around 9/11. Pew Charitable Trusts polling data tells a similar story. Congress’s favorability rating looks a lot like a kid’s slide with a big bump in the middle.

Source: Pew Research Center report.

Zooming out, public trust in government appears to have collapsed. In 1958, 73% of Americans trusted the government in Washington all or part of the time. In 2015, of 19% of Americans have that same level of trust. (According to Pew.) Of course, it’s not a steady decline, with the changeover in administration and national calamities creating a surge of approval.

Why has the government’s approval rating fallen so much? In part, the Vietnam war and exposure of the perfidy of the Nixon administration can be attributed much of the initial decline, from 77% in 1964 to 35% in 1976. But why would it never again go above 50% except for momentary spikes?

Presumably there are many reasons. I would imagine among the top are an end to blind faith in our leaders, a willingness to view their actions with a more careful (or caustic) eye, and an increased polarization in our politics that makes it less likely to trust leaders of the opposite party. (Of course, there were some people who wanted to increase partisanship so that voting for a party meant something — but that’s a digression for another time.)

What does this mean for Congress? To start, people like their congressional representative a whole lot better than Congress as a whole. In a neat graph, the blog FiveThirtyEight shows that ratings for individual members tend to run about 25 points higher than Congress. (Sorry, I cannot reproduce the chart here because it’s copyrighted.)

It’s not a tremendous surprise that individual members of Congress are more popular than the institution. My research indicates individual members of Congress has shifted their staff over the last 25 years to focus on constituent service work and press relations and away from policymaking. That’s bad for democracy but good for reelection.

We also see many members of Congress “running against Washington.” Only a politician intent on career suicide would quote Adlai Stevenson and declare “your public servants serve you right.” Nowadays, only a retiring member of Congress can dare suggest, for example, that Members of Congress aren’t paid enough. He’s right, and that’s not the half of it.

Congress’s Governance Problem

No one sticks up for Congress as an institution, and great harm come from our collective disdain. Congress’s funding has been cut to the point where it is the shadow of the institution it once was. Its belt has been tightened past asphyxiation. Congress no longer can properly oversee the executive branch. The number of personal, committee, and legislative support agency staff are way down — and are far younger and less experienced than their counterparts of a few decades ago. (See House and Senate data). I’ve written elsewhere, only slightly tongue in cheek, that we should triple the number of staff and double their pay. And Congress’s technology — and technology spending — is woefully inadequate.

There is a potential way out of this downward capacity crunch. I wrote about that path in a series called “Congress Can Fix Itself… With a Little Help.” I argued, in part, that:

- Congress must systematically gather and make accessible to all staff all the information it collects regarding government activities;

- Congress must do the same for legislative/congressional information;

- Congress must reexamine workflow management (for individuals and groups);

- Congress must better engage with the public.

All of these things rely upon the better use of technology. Congress has not integrated the information revolution into its operations, with predictable results.

What I did not emphasize in the articles were the twin issues of funding and transparency. I have argued elsewhere and at length the need for greater investment in Congress, which receives less than 1% of annual federal spending, and much of that goes for non-legislative functions.

Transparency Matters

But, why does transparency matter? To start, in a democratic government, transparency should be the default. I realize this has become a somewhat controversial position of late, but there’s a reason why I think so. People must be able to see what their government is doing in order to know whether it is functioning properly. Moreover, it’s hazardous to tinker with something unless you understand how it works. Of course, some things should remain secret — the idea of naked transparency is a straw man — but their effects often will come into public view.

The ability to look at legislative activity as a whole — the number of and substance contained in bills, the text of amendments, the hearings and markups, voting patterns, staff retention patterns—can act as a gauge to determine whether productive legislative activity is taking place. There have been attempts to create a broad index along these lines — such as the Healthy Congress Index —although methodology is too coarse to be useful at this time. Even so, more granular data about Congress combined with better tools and clever approaches could yield potentially useful results. Even now, it’s possible to get a narrow view into some aspects of how Congress functions, as Tom Mann and Norm Ornstein have demonstrated.

In addition, the ability to look at the nitty-gritty of legislative activity empowers voters to weigh on the issues they care about, and to hold their elected officials accountable. Many websites make this possible, most notably GovTrack. It’s unlikely that many voters will directly engage at this level of detail. For those that do, I suspect a weakness in the accountability mechanism may lie in crudeness of our voting system.

Nevertheless, proxies for voters — advocacy groups, think tanks, journalists, and citizen bloggers — will engage with the details of legislative activity and filter it out to the general public. (The decline in funding for professional journalism has weakened one of these legs, but as we have seen with the Supreme Court and SCOTUSBlog, there are emerging remedies for this problem.) A responsive release by Congress of highly processed information about policy matters — such as CRS reports, agency reports to Congress, budget information — will provide necessary information to explain Congressional activity in layman’s terms. Similarly, transparency into the inflows of money into candidate campaigns and how they vote provides a sense of how representative of our interests our representatives are.

Combating Cynicism

One danger in a democracy is cynicism that arises from a sense of corruption. While we still occasionally have a member of Congress who keeps a bag of money in his freezer or remakes his office as Downtown Abbey, we no longer have with the same frequency the fascinating and awful stories of quid-pro-quo corruption as recounted by LBJ’s Senate fixer. Although, as the Panama Papers indicate, we’re not out of the woods yet. And there’s plenty of corruption in the form of revolving door, influence peddling, and cash-for-access.

The current campaign finance and lobbying systems casts a harsh light on our elected officials. In addition to the hard slog of resolving those issues, there are smaller, simpler steps that can reduce their effects. For example, we could prohibit members of Congress from personally engaging in fundraising activities during days Congress is in session. We could also decrease the reliance of members and staff on lobbyists by strengthening congressional institutions and paying staff more. Many tiny steps can get us far down the path of ameliorating some of the causes of cynicism by addressing its basis in fact.

We can also change how the ethics process works in Congress, drawing from principles elucidated in behavioral economics, so that members of Congress have the incentives to follow the straight and narrow with systems in place to make it easy(ier) for them to stay in line. Dan Ariely’s book The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty and Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow should be a bible to rethink how our ethics system should work. As it turns out, something as simple as requiring people who fill out ethics forms to attest to the veracity of its contents when they begin the form, and not at the end, improves its accuracy tremendous, with real implications for oversight and investigation. (See Predictably Irrational, chapter 13, by Ariely.) A symposium on governance and behavioral economics would do everyone a world of good.

Civil society has many roles to play when it comes to addressing cynicism. For example, we can celebrate when people do right, like at the upcoming Doorstop Awards. We can partner on technology with government officials to help them modernize congress, and build tools to empower them and civil society, like we’re doing through the bipartisan Congressional Data Coalition. We can give specific advice, like how to change the House and Senate Rules, or to open up the legislative branch, or to gather better information from the agencies, or even strengthen a particular committee. And we can be an honest broker, especially when perceived allies falter. There’s a role in this space for non-partisan, partisan, and omni-partisan organizations and coalitions, and for learning from our international friends. The biggest weakness in the civil society space is a lack of capacity to deepen these efforts and retain experienced staff.

A mountain or a molehill?

Will any of this change how Congress is perceived? Maybe. There are no guarantees. Better data on Congress does can point us down the right path. And a better functioning Congress should lead to better outcomes — or at least outcomes that are widely perceived as sensible and legitimate.

And that, after all, is the purpose of Congress: to aggregate preferences and create policy that is viewed as sensible and having democratic legitimacy. Our representatives probably cannot earn the people’s love, but perhaps we can help them rebuild a sense of respect.

— Written by Daniel Schuman